The ITM Community: Part II, Information seeking behaviors and the Serious Leisure model

An MLIS Case Study

In my last post on the Irish traditional musician (ITM) community I examined how the community itself fits within the various Library and Information Science (LIS) descriptions of an Information Community (IC). Now that we have framed them within those parameters we can begin to assess how they go about fulfilling their information needs. To do so I’ll look at two models, that of serious leisure, as defined by R.A. Stebbins (2001), and the concept of berrypicking, as detailed by Marcia Bates (1989).

I’ll start by analyzing the nature of serious leisure and explain how the ITM community fits within the criteria. According to Stebbins serious leisure can be defined as, “the systematic pursuit of an … activity that participants find so substantial and interesting that, in the typical case, they launch themselves on a leisure career centered on acquiring and expressing its special skills, knowledge, and experience” (2001, p3). In addition to this, Hartel (2003) speaks on the level of significant effort one must make to maintain membership in this community through the acquisition of knowledge and skill. I can personally attest to witnessing musicians at their first session compared to years later. I can even include myself in this description as my first venture into this community was in summer of 2018. The community at large is highly suspicious, albeit quite welcoming, of newcomers. The concern is of course, how much does this new person care about the community? How much effort will they put into becoming a good musician and good session player? This mentality demonstrates the level of commitment and devotion each musician has for this community. One of the most common questions asked of anyone when they walk into a session is, “what tune have you been working on?” There is an expectation from all that each of the community continues to grow and invest their time and energy into the community.

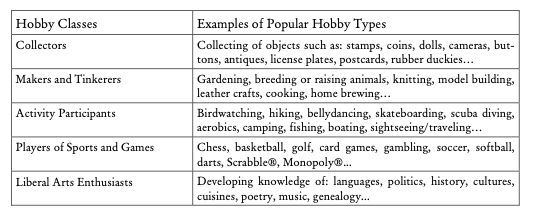

Figure 1. A chart detailing the various topics related to the five categories of serious leisure. (Hartel, 2003)

According to the chart in figure 1, we can see clearly that the ITM community fits within the primary category of liberal arts enthusiasts. The musicians may originally arrive in the community through any number of the topics listed. Language, history, genealogy, or the music itself. But the longer one spends in this community, the more involved with each they become. And as expressed by Hartel (2003), they may even develop aspects of the other categories, such as collecting musical instruments or old music collection, or tinkering with the instruments they collect.

We can see how the ITM community fits within the classifications of serious leisure, and through that lens we can begin to look at how the community addresses their information needs. Of all the topics listed in the category of liberal arts enthusiast, music is obviously paramount to the ITM community. And as such, the need to learn music is the primary information sought. However, due to the very nature of folk music there is no one singular source of truth for such music. In fact, if you were to search for the well-known Kerry polka on thesession.org, you’d see 6 distinctly different names for the tune paired with 15 different settings (Figure 2). It makes sense then that the concept of berrypicking has particular value for understanding the information seeking behaviors of the ITM community.

Figure 2. A screenshot of thesession.org showing the uniquely different names of a single well-known tune. (2024)

Through personal experience I can present a hypothetical overview of how many in the modern ITM community search for music and information about said music. The process usually begins at the session itself. Someone will inevitably play a tune another has never heard before. Someone will ask what it’s called. The person who started the tune may or may not know the tunes name. In many cases they will give an approximate name. It may also be an Irish gaelic name which no one can remember how to spell. If you are really lucky, they may give you an album and musician from where they learned it themselves. All these little bits of information are what trad musicians begin their search with. This is the first aspect of information seeking behavior that relates to the berrypicking method. The individual may not always know exactly what it is they are looking for.

If we compare this initial stage to the model of berrypicking outlined by Bates (1989), we can consider this query zero, or Q0, the initial point of the search. Let us continue with the example of The Kerry polka. If this tune were played at a session, someone might identify it as Egan’s polka, or the East Limerick polka. With this information a musician can begin their search. Many will use thesession.org as their starting point. On thesession.org one can find a multitude of things associated with the names given at the session, including learning that the polka in question is most often called The Kerry polka. Now that they know a more common name for it, they can begin to search for an ideal setting of it. They may then look through a personal collection of music to see if is there, and if that version resembles the one they heard. Thus, they begin to compare the two version, online and print. Or, if they are unable to read sheet music, as is the case with many in the ITM community, they can find popular recordings of the tune. At this point we have not only found our first documentation, but begun to ask our second query, or Q1 as detailed in Bate’s model.

Figure 3. A map of a berrypicking/evolving search as depicted by Bates (1989).

At Q1, the musician might begin to wonder which of these sets or recordings is most like what they heard at the session. So, they will often expand their search to find a version of The Kerry polka that most closely aligns with the version they heard. This step could be searching through the various recordings of the tune in question. Another query that may arise is, why the various names? This may prompt a search about the tune’s history and etymology. Thus, taking the musician down another path in search of knowledge. This pattern may continue for any number of queries until the musician has learned enough about the tune to be able perform it with confidence at a session, as well as be able to converse with their peers about the tune.

This quest for information has the potential to branch of in many directions, all of which started from one origin, hearing a specific tune at a session. From there, one may begin to research other tunes to pair with the first. They may stumble upon documentation about music of the region from which the tune original came. All of these bits of information support the concept of serious leisure, as the musicians make a significant to learn not only to improve their own music playing, but to develop a deeper connection with the culture and community itself.

References

Bates, M. J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Review, 13(5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb024320

Hartel, J., Cox, A. M., & Griffin, B. L. (2016, December). Information activity in serious leisure. Information Research, 21(4). http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper728.html

Stebbins, R. A. (2002) New Directions in the Theory and Research of Serious Leisure. Contemporary Sociology, 31(3), 371. Sage Publications.

The Session (2024, February 25). The Kerry polka. Thesession.org. https://thesession.org/tunes/39